Arts

Knowing our mothers

In ‘some things in the belly’, artists try to understand mothers beyond their roles, through letters, moving images, films, poetry, and installations.

Deepali Shrestha

I remember looking at my mother’s photos from her college days in an old 90s-style album in Dharan. In one photograph, she is surrounded by a group of girls in Biratnagar, all wearing kurtha surwals in the same shade of blue. She has a soft smile, and her youthful face looks almost too delicate. Whenever I see these photographs of my mother, captured in a life I never knew, I feel an unease that I can’t quite comprehend.

Who is this young woman I was seeing? Why does she feel so familiar and distant at the same time?

Bunu Dhungana tells me that we spend much of our lives never truly knowing who our mothers are beyond the roles they play. We even forget that our mothers have names other than ‘Maa’, ‘Aama’, or ‘Mummy’, or other titles we call them.

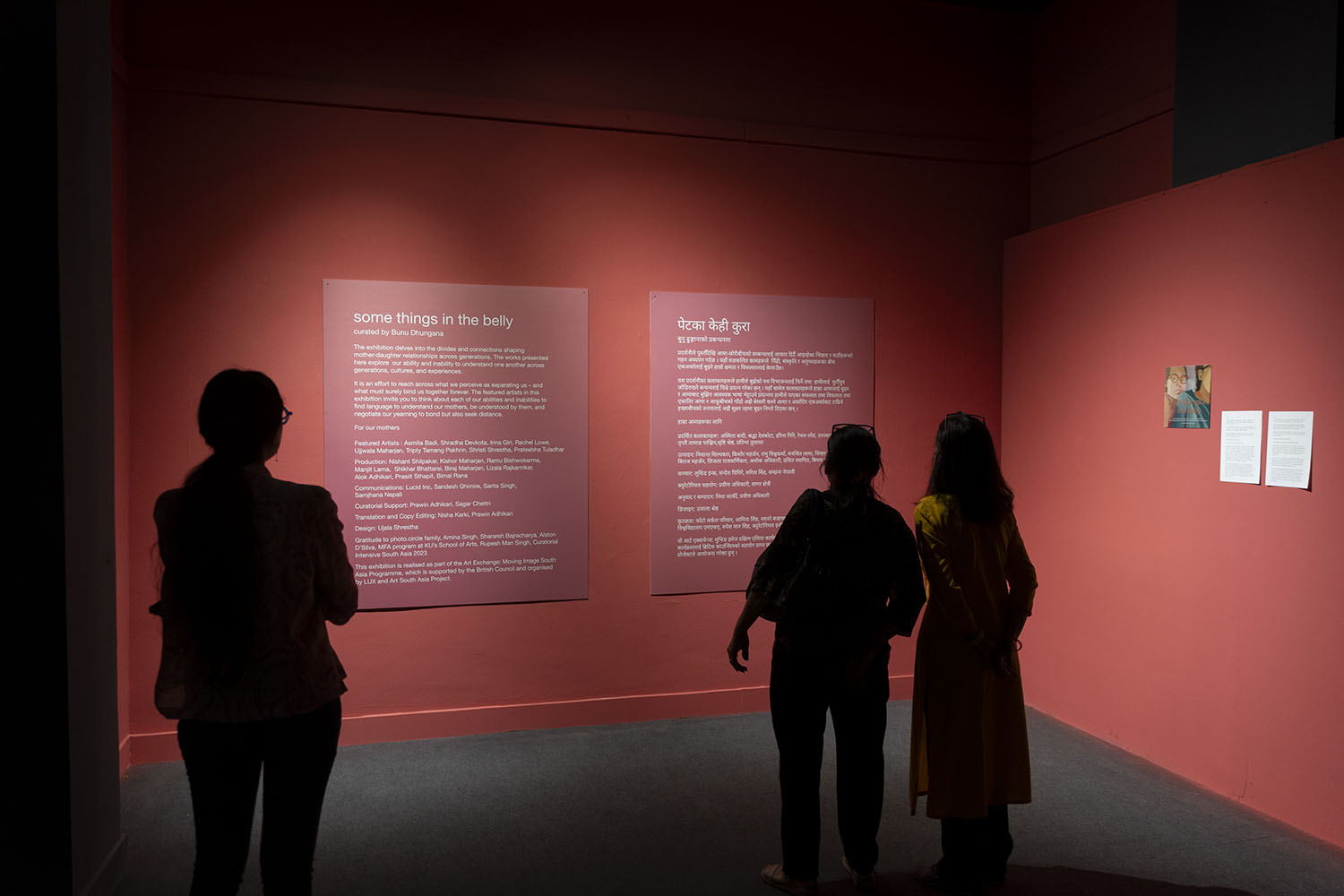

Exploring the intricacies and complexities of the mother-daughter relationship is the essence of the exhibition, ‘some things in the belly’, happening at the Nepal Art Council. Dhungana has curated a space where mothers and daughters try to find a language through letters, paintings, installations, poetry, short stories, moving images, films and performances to understand one another.

The featured artists are Asmita Badi, a poet and activist; Tripty Tamang Pakhrin, a visual artist; Shradha Devkota, a multi-disciplinary artist; Ujjwala Maharjan, a poet, performer and educator; Prateebha Tuladhar, a writer, storyteller and educator; Shristi Shrestha, an artist; Irina Giri, a multidisciplinary artist and Rachel Lowe, an artist and filmmaker.

Dhungana believes that the love we have for our mothers is unmatched. “The spectrum of emotions we feel for mothers is vast,” she shares. “I can’t think of a love that comes close, not even romantic. What could be greater than our love for our mothers?”

At the opening, after listening to educator Amina Singh reflect on motherhood and watching Maharjan and Badi’s performances, I sensed that the journey the exhibition was about to take me on wouldn’t be easy. As I walked through the exhibited works, this feeling deepened into certainty. Each artist attempts to unearth the unspoken emotional undercurrents constantly flowing between mothers and daughters and the love that thrives within this tension.

In her previous works, Dhungana had already begun exploring the theme of mother–daughter relationships. In her photo exhibition 'Confrontations' at Photo Kathmandu 2018, she explored the relationship between herself and her mother, with a letter her mother wrote to her serving as a central piece. The idea of the letter stayed with Dhungana. Later, when she received the Khoj International Artists’ Association fellowship, she hoped to build on the theme of mothers and daughters, exploring its many meanings through different medium.

She invited artists, gave them a prompt, and observed how the process would unfold. After exhibiting this in 2023 in New Delhi, Dhungana envisioned bringing the project home. She was later selected for the Art Exchange: Moving Image South Asia Programme. Over the next two years, her vision gradually came to life through online meetings with the artists, where they reflected on their relationships with their mothers that are universal, yet so often taken for granted.

“There were many things about society that angered me. Even as the anger is still there, I am finding ways to express it differently now,” says Dhungana.

After entering the exhibition, there is a video of a woman struggling to pull a long, blank sheet of white paper as she climbs the stairs. A hand holds another hand sculpted from ice, which is melting away. This may be what it means to embrace and understand our mothers as they age and become fragile. As daughters, this can frequently become a frustrating and painful experience, even when we feel a sense of urgency. We struggle, negotiate, and embrace, and in the process, we slowly come to terms with the reality that we are becoming reflections of our mothers. Devkota depicts the layers of time, love, longing and loss surrounding our relationship with mothers through the videos in her work, ‘The Urgency of Now’.

On one side of the exhibition stands an old, boxy TV, its screen resembling the window of a moving vehicle through which the landscape continuously changes. A hand scribbles on the window as if trying to draw something, but failing each time. Incompleteness seems to be important to Lowe's work, ‘Letter to an Unknown Person No. 5’, and its ambiguity makes it open to multiple interpretations. This may explain why it echoes the mother-daughter dynamic, often filled with unresolved and uncertain instances.

During a conversation with the artists at the exhibition, Shrestha recalls the pandemic days, when she felt a sense of collective care with her mother and sister through their evening Zumba sessions on the rooftop. These moments planted the seed of her paintings, and she became more conscious about the care and warmth surrounding her mother and aunts. Her work, ‘Take Care’, shows everyday moments of tenderness between the women around her, reminding us of the uncertain times when all we had was each other to care for and hold on to.

What is the meaning of mother, and what does it mean to have one? This is a recurring question in ‘some things in the belly’.

However, Badi’s response during the conversation with the artists touched me. She said that she understood the meaning of mother when her mother scavenged raw corn and boiled it to feed her when there was nothing to eat. She shares her personal stories with vulnerable honesty, and the same emotion runs through her poem ‘Is Life but Breath’. She writes about her mother’s sacrifices and struggles by asking whether life is only breath, as her mother hasn’t lived her life while she breathed.

A few lines from the poem read:

‘Otherwise, mother is full of courage. She is capable of burying inside her eyes all remnants of her existence, she can cling to a fistful of air and continue to breathe.’

Dhungana recalls that she met Badi through Maharjan, “When I met Asmita, I was awestruck. I wanted to know more about this woman with a fire in her belly.”

Maharjan has moved people with her poetry, which is anchored in her roots, and evokes a sense of community and challenges misogyny. Through her words, performances, and installations in ‘What I wish for You’, Maharjan takes us into her journey as she navigates life as a woman and becomes vocal through different art forms about the shared experience of becoming sisters, aunts, mothers and daughters. The low table, scattered with books on different aspects of womanhood and culture, gives us a sense of community and belonging, as well as a space to rethink learn, and unlearn the ideas we hold about ourselves.

Giri’s interpretation of the poems ‘Naniji’ by Itisha Giri, ‘Snow Theory’ by Ocean Vuong, and ‘Morning Song’ by Sylvia Plath through sounds in ‘The Mothers Selves’ adds a different dimension to the exhibition, allowing us to feel the sensations of the rhythms of life with our mothers.

I often fail to realise that certain things I’ve had since childhood have never existed in my mother’s world. This feeling emerged again when I saw ‘A Desk of One’s Own’ by Tuladhar. During the conversation with the artists, she said that her mother reads a lot, but she never had a desk. In her work, she imagines a desk for her mother and places on it the books her mother reads—such as 'Seto Dharti' by Amar Neupane, 'Kumari Prasnaharu' by Durga Karki, and others. This is the story of many mothers who have to use sofas, dining tables and kitchen slabs to read and write. On the desk sits an old laptop containing personal letters to her mother, in which she writes about how she remembers her mother in her daily life. A used coffee mug sits beside the laptop, allowing one to catch a whiff of coffee and feel welcome.

On the bookshelf on the wall beside the desk is a collection of books on mothers, daughters and feminism that Dhungana has been reading over the years, such as 'All About Love' and 'Feminism Is for Everybody' by Bell Hooks, 'The Woman Who Climbed Trees' by Smriti Ravindra, and others.

In a 12-minute video, Pakhrin takes us to Hotel Thai, a restaurant and lodge where she grew up, on the Nepal-India border. In the video, the spaces between frames echo the voids and unspoken silences between her two mothers—women who have coexisted for years within carefully maintained boundaries. Her narration carries an eeriness, so soft yet haunting, that it lingers in the ear. ‘Untitled (Welcome to Hotel Thai)’ allows us to understand mothers and motherhood through privacy, ownership, shared responsibilities and unspoken language.

Letters are at the heart of ‘some things in the belly’, where confessions, apologies, confrontations, and other forms of expression find a place. Perhaps this is what drew people in, offering them the comfort of penning down their letters to their mothers.

In her letter to her mother, Dhungana writes, “I am sorry. I only saw you as mother. Not as the woman you are.” We learn to apologise at a young age from our mothers, but somehow, it becomes increasingly difficult to say sorry to our mothers as we age. However, seeing the exhibition wall covered with apologies and thank-yous to our mothers is perhaps the most beautiful part of ‘some things in the belly’.

“I manifested that people will write heartfelt letters and fill the letterbox and the wall. Now that we have stacks of these unfiltered love letters to mothers, I am so moved, I don’t know what to do with these feelings now,” says Dhungana.

some things in the belly

Where: Nepal Art Council, Madan Bhandari Road, Kathmandu

When: May 3 to May 16

Time: 11:00 am to 7:00 pm

Entry: Free

17.29°C Kathmandu

17.29°C Kathmandu.jpg)